During one of our family trips to Srinagar in 2016, we got house bound as there was a two week

long shutdown of the valley due to the death of a beloved militant who greatly appealed to the

youth. We live in Delhi, 90 minutes by flight from Srinagar, and this complete lockdown made us

acutely aware of the freedom we take for granted.

Kashmir has been a contentious issue between India and Pakistan for 72 years. However, the

last 30 years have been marked by conflict and today, Kashmir is the most militarized zone in

the world. This work is a reaction to our experience at the time and a deeper reflection of what it

means to live in an environment, which is heavy with a sense of betrayal and subjugation. We

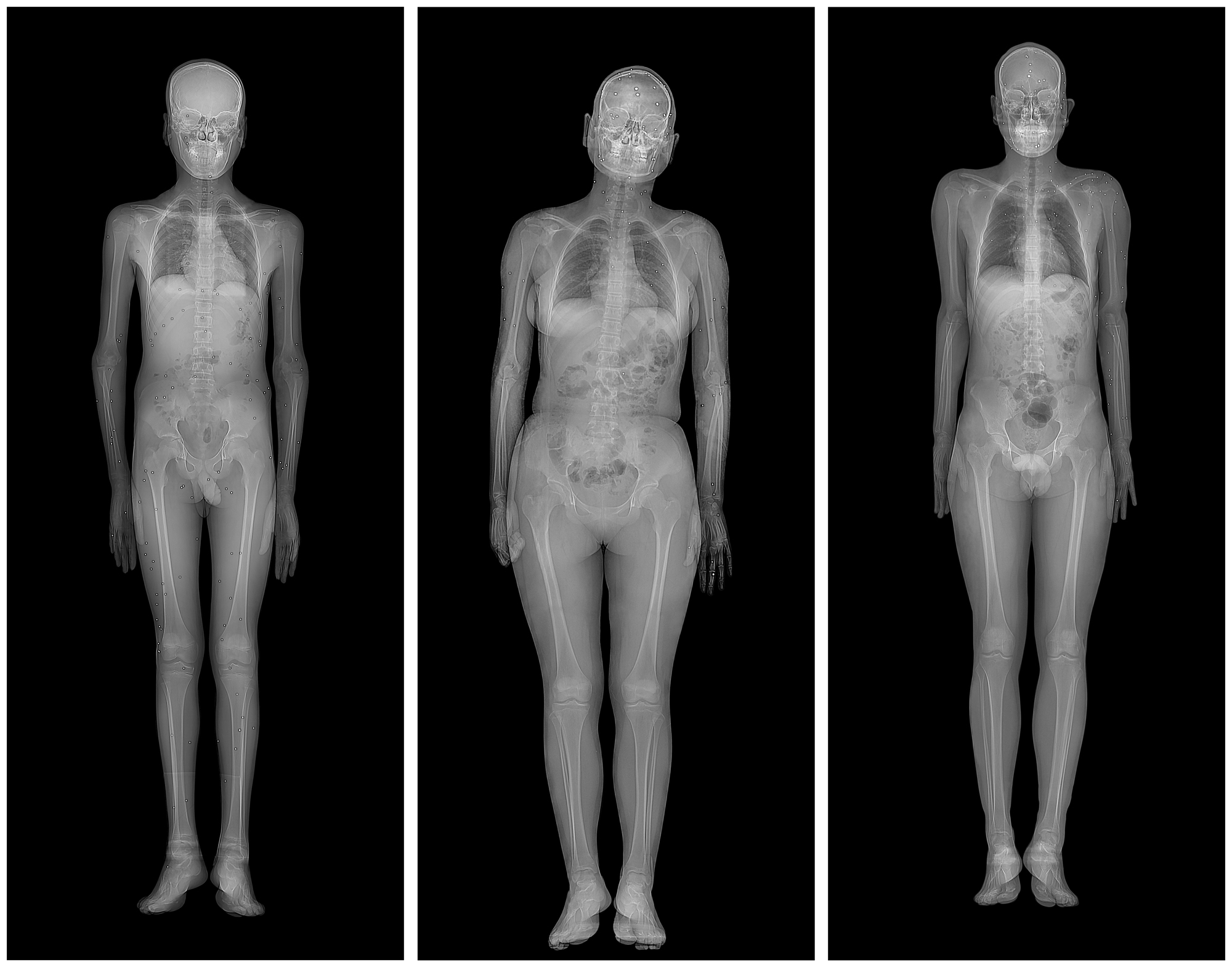

started with making portraits and x-ray portraits of the victims of pellet guns. The state

sanctioned the use of pellet guns, which are described as a ‘non-lethal’ crowd-controlling

weapon. However, the use of these guns has led to thousands of people getting maimed and

hundreds blind.

This vitiated atmosphere is a grim reminder of why Imran, my partner and other boys his age

were sent away from Kashmir in the 90s while still in their teens. One has had to accept that for

children born into conflict — curfews, lockdowns, extra-judicial killings have become the normal.

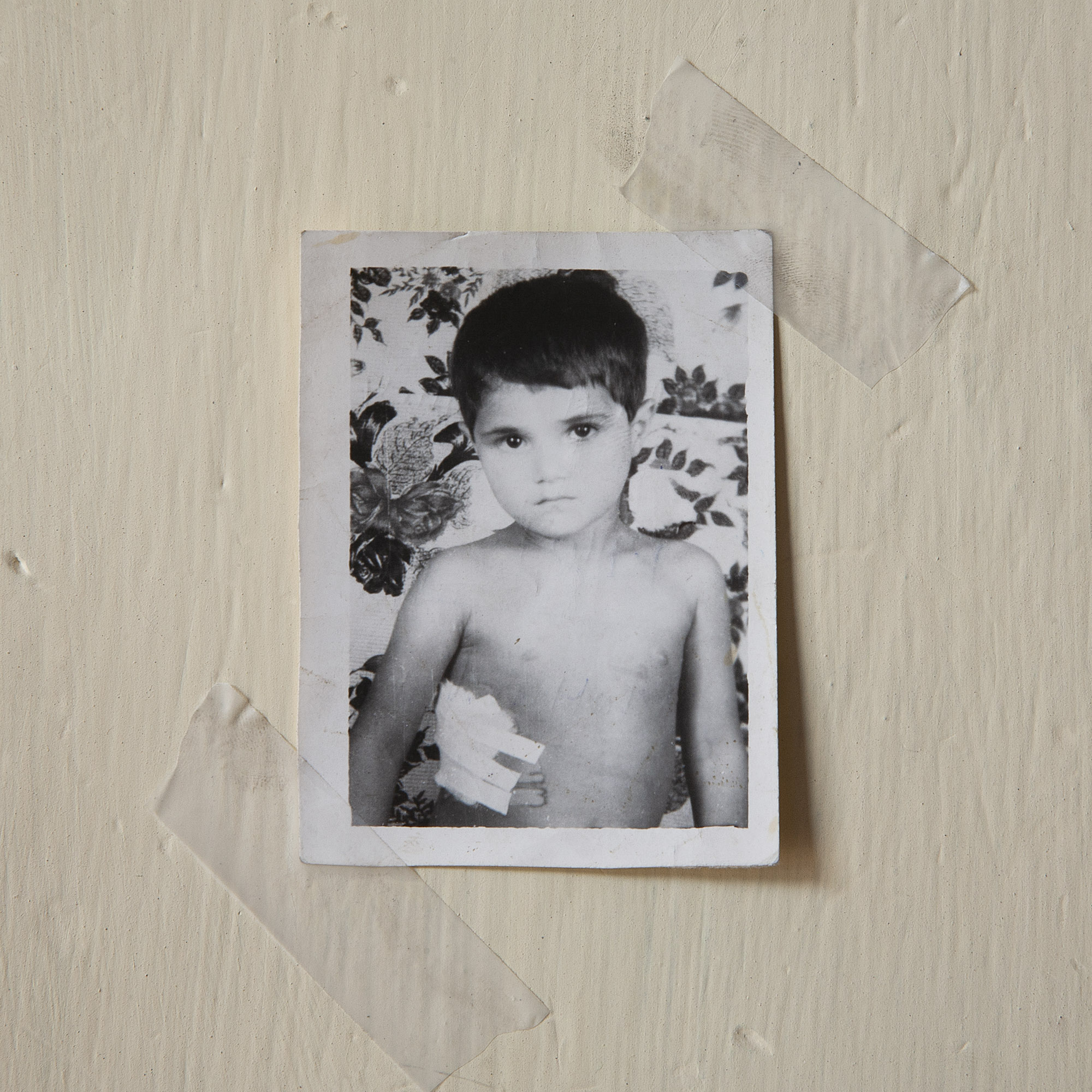

How does one measure the loss of childhood during any kind of conflict? The fact that two

generations of Kashmiris cannot dream a dream not marred by conflict is very sad; the sub

conscious is dominated by violent memories and the natural instinct to survive often gets

subverted. The desire to hit back increasingly overrides the instinct to live.

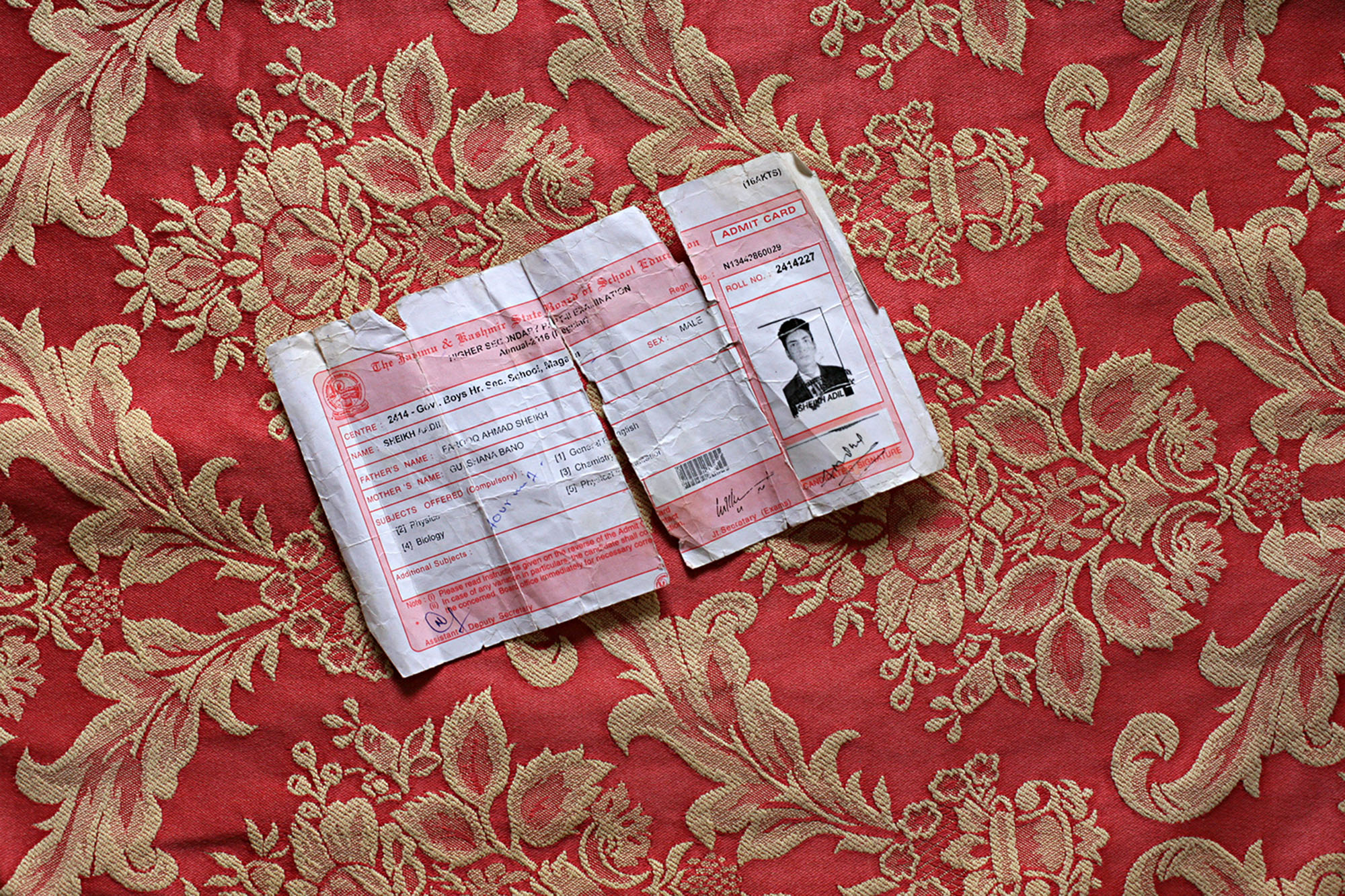

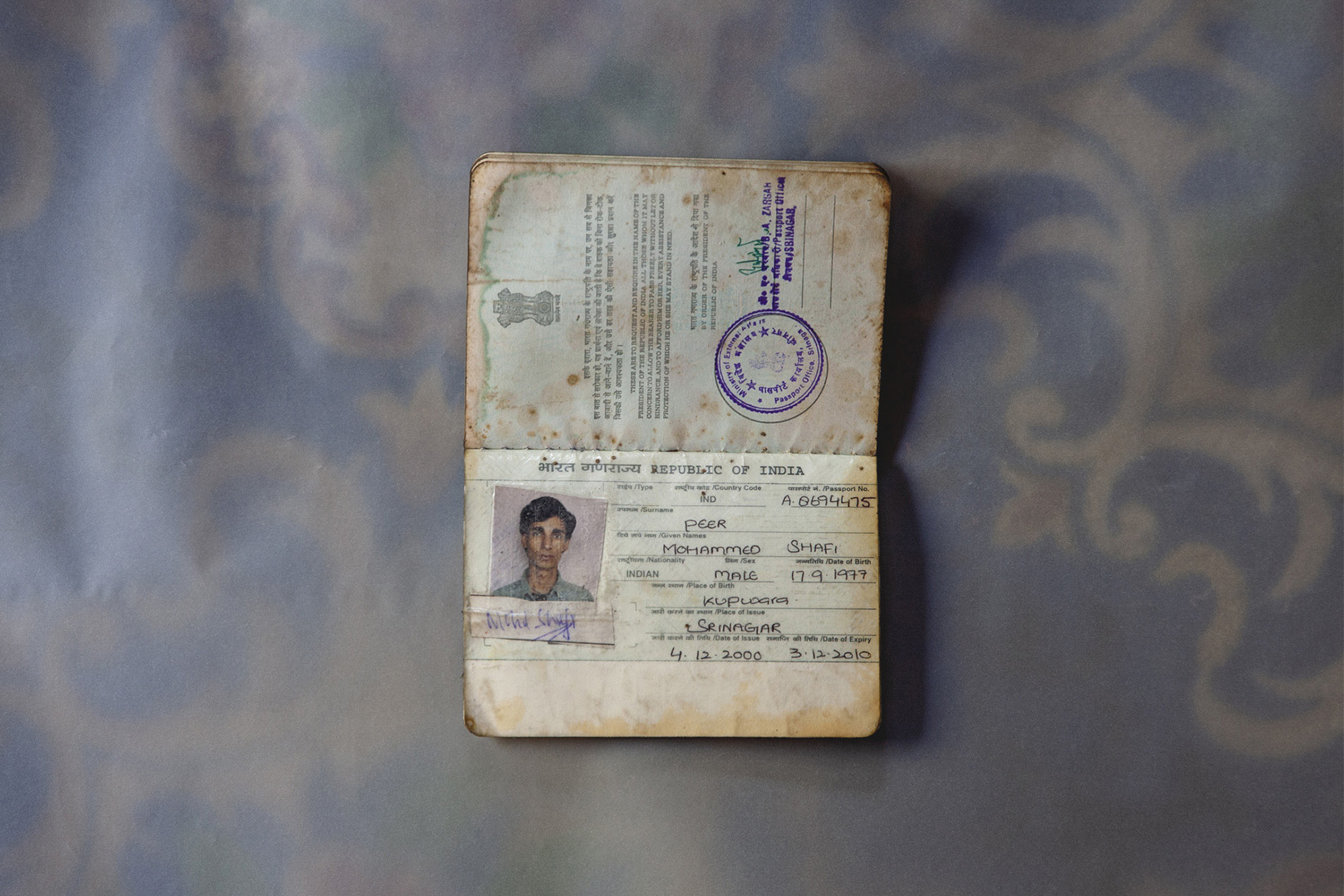

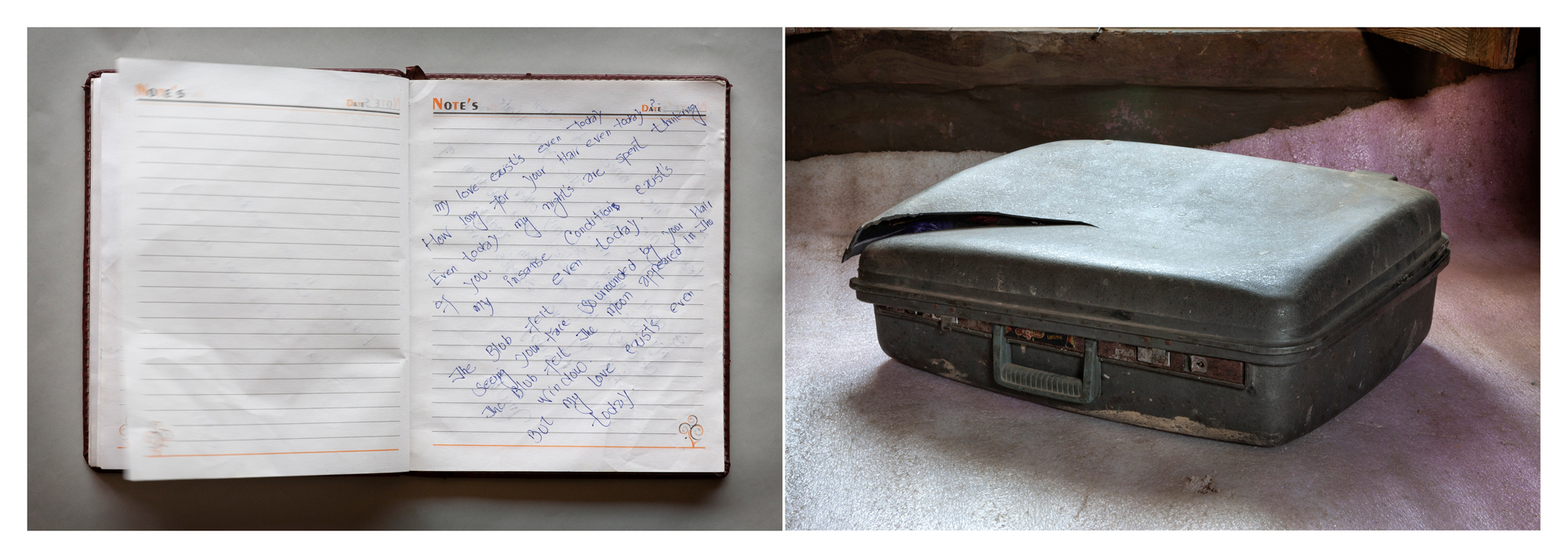

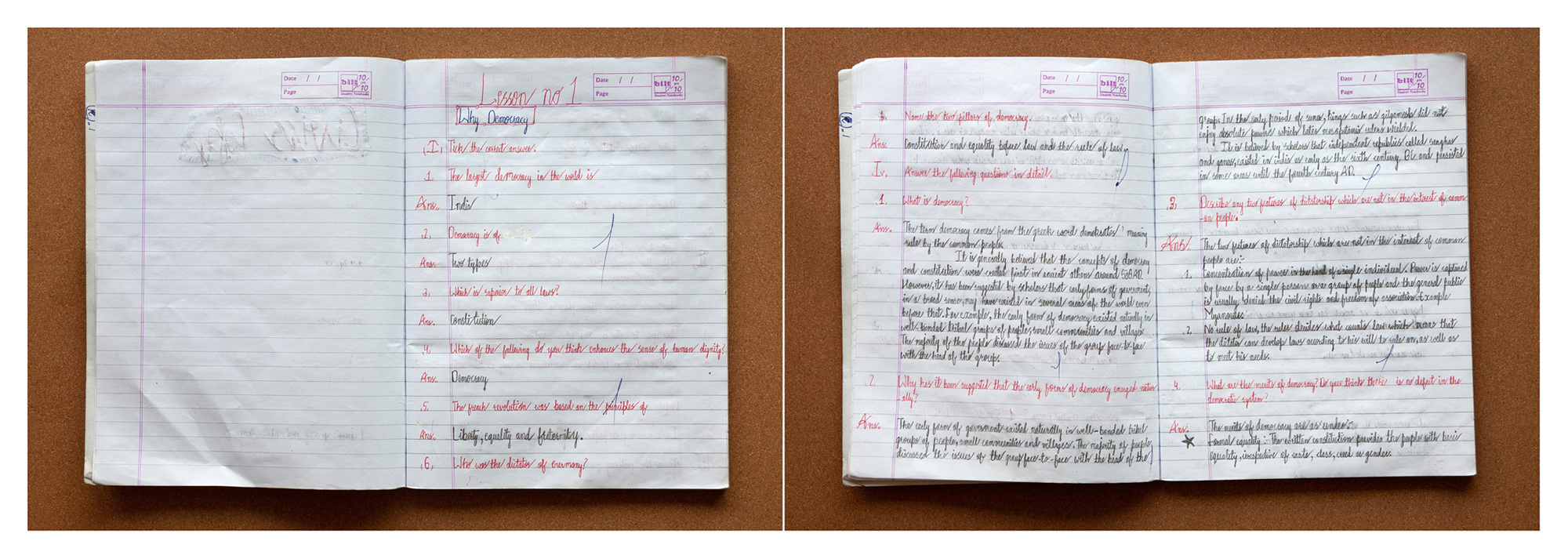

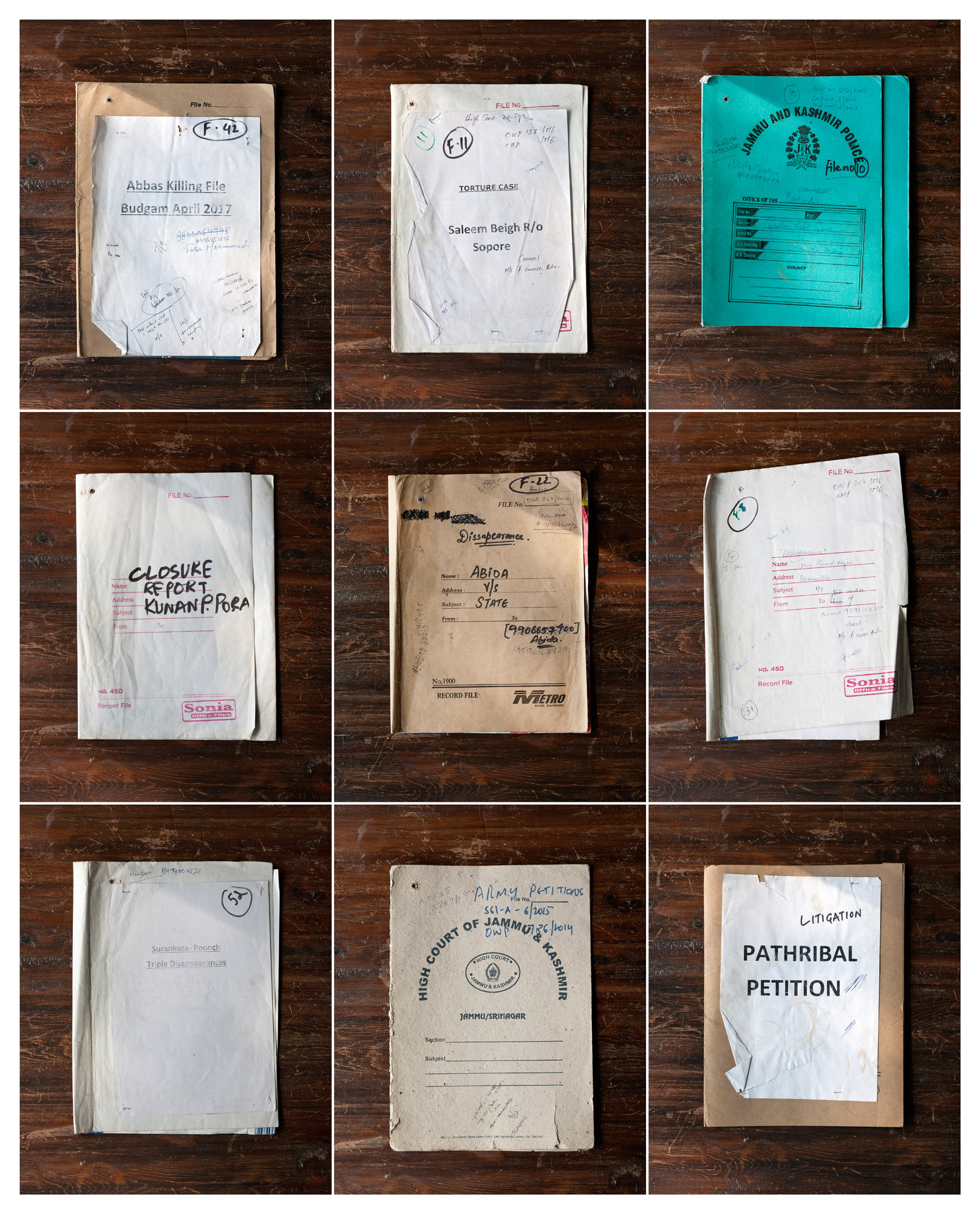

This work has now further evolved. The landscape has been photographed using pinholes to anchor Imran’s memory of his home. The tropes of memory — clothes, notebooks, identity cards, photographs and other belongings that families treasure are being documented. We continue to collect documents exchanged between families & the establishment (the sense of helplessness that arises from their content, borders the Kafkaesque).

In Delhi, our daughters sleep with absolute abandon, which is in stark contrast with the images of violence and depravity we see on our screens daily. However, my family shares the canvas with the larger story of Kashmir even as we live in a sense of psychological exile. Hence our own family album finds its space in this work as a grim reminder of the innocence and normality lost. Even though the conflict is a part of our history and continues to be a part of our daily existence, it is unfortunately not a part of a larger collective memory outside of Kashmir.

(This is a collaborative work by Anita Khemka and Imran Kokiloo)

Visual Portfolio Submission — Documentary Media MFA, Ryerson University

I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell — a lost childhood

Zero Bridge

Zero Bridge Cemetery

Cemetery X-Ray Portraits of Pellet Victims

X-Ray Portraits of Pellet Victims Portraits

Portraits Identity

Identity Youth

Youth Protest

Protest Belongings

Belongings Displaced

Displaced Untitled I

Untitled I Untitled II

Untitled II Court Files

Court Files Home

Home Found

Found School

School